Basquiat & Penck, World-Makers, by Matthew Holman

A. R. Penck and Jean-Michel Basquiat were masters of making worlds in their paintings, drawings, and works on paper. Each used complex and idiosyncratic visual languages, which often incorporated hieroglyphs, ideograms, and textual-visual spillovers, as they sought to make sense of their troubled historical moment. Many of the works in Basquiat & Penck: Works on Paper address how each artist’s analytical and pictorial thinking coalesced, specifically in relation to the self-portrait tradition and the anxieties of representing their fraught Cold War moment. Despite their striking formal correlations and a friendship forged in the frenetic downtown scene in 1980s New York, Penck and Basquiat have seldom been seen in correspondence with one another. This exhibition display situates their works on paper together for the first time.

When Penck emigrated from East to West Berlin in 1980, it was the first of several geographical and artistic crossings the artist made over the ensuing decade. On the many occasions that he would visit New York, where he began to show at the Sonnabend and Mary Boone galleries, Penck arrived in a city that knew his name. On the Lower East Side, he found an environment that spoke to his idiomatic graphic language of ‘Visuelles Denken’, or visual thinking. In the downtown scene, Penck has most often been seen as a mentor to Keith Haring, with whom he helped inspire a practice of drawing stickmen (in Penck’s case, spindly and Giacometti-like; in Haring’s, rounded and full-bodied). However, Penck’s friendship with Jean-Michel Basquiat, and its role in shaping their collaborative ethos, a common mode of sign-making, and their remarkable shared practice of eccentric world-building, remains one of the untold stories of post-war painting in New York.

Penck’s case artistic identity was shaped by the Cold War, having been excluded from the Academy in Dresden and the official art market in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), which favoured an internal market devoted to realism. He was increasingly disillusioned with the utopian socialism that had kept him in East Berlin for so long, despite his resistance to state authoritarianism, and had developed what he called his ‘World’ and ‘System’ paintings. These were motivated by the division of Germany on ideological lines, and his long-held aspiration towards a universal language of signs and signifiers that became known as his ‘Standart’ concept. Uniting word and image, and organised around primitive or childlike imagery, ‘every Standart-Bild is capable of being reimagined and reproduced, to become the property of each individual’, Penck said in 1970: ‘What we have here is a true democratisation of art.’

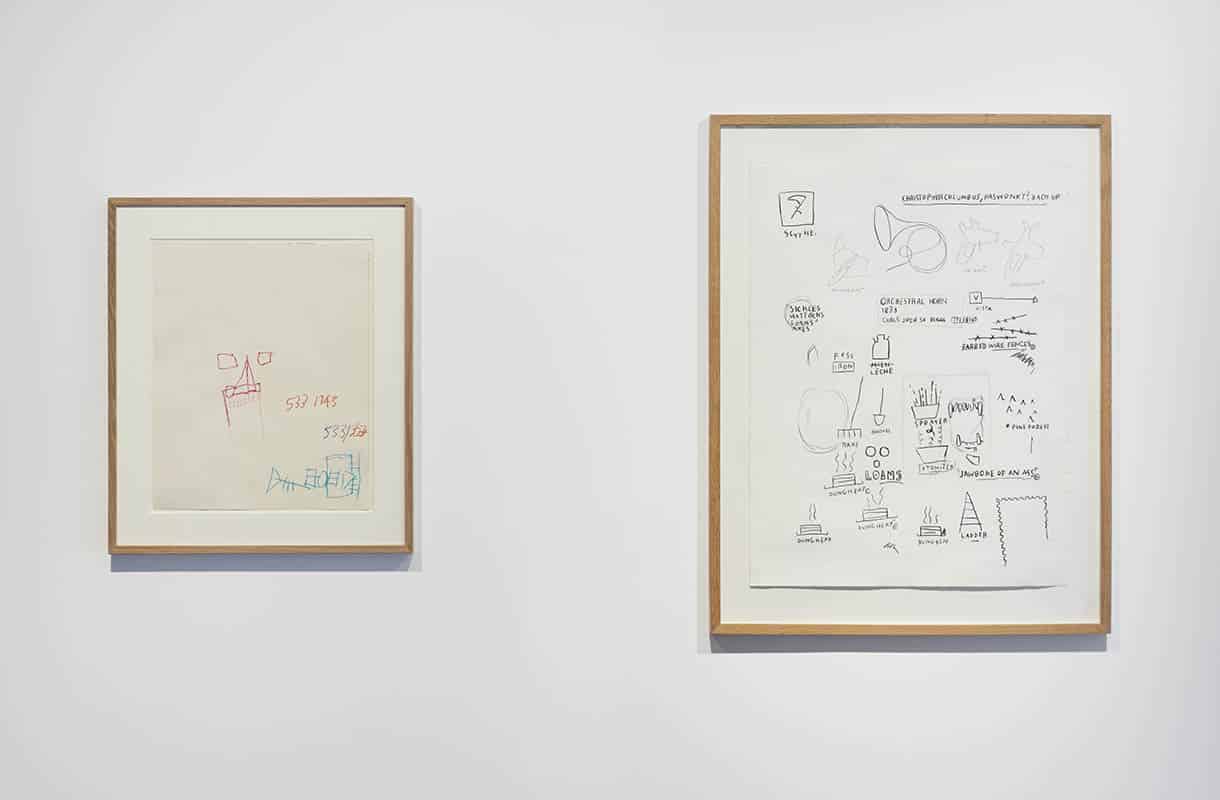

This sense of the radical possibility of art-making and individual transformation animates his works on paper and finds a provocative and compelling counterpoint in Basquiat. In Untitled (1987), produced in the year before his death, Basquiat depicts an apparently unrelated compendium of diagrammatic images with captions. Taken together, they represent a mixture of exoticism and inhospitality and conjure a world of irreconcilable tensions. A king cobra is placed below ivory false teeth, a sun (burning at 15 million degrees centigrade) would seemingly incinerate the Arctic lemming, and the perpetual suffering of whoever is ‘only allergic to the dust in their own homes’ suggests a place we can no longer live, and yet struggle to find a way out of. Similarly, Penck’s figures often seem contained and hemmed in by impossible environments. In Untitled (1994) a stickman, holding what seems to be a double-sided arrow and multiple hammers, is subsumed within a matrix of blue spheres and red rectangles, suggesting parts of a mechanised world gone awry. Both works imagine hostile and constricting worlds, zeroing in on the individual experience.

Throughout the early years of the 1980s, Penck and Basquiat obsessed over how to reduce, simplify, or otherwise transform the self-portrait into its fundamental terms. In this regard, they find in common an illustrative language that embraces the referential directness of the cave painting, the expressive spontaneity of the graffito mark, and the utility of the anatomical illustration. In Untitled (Self Portrait) (1980), Penck envisages himself in well-defined daubs of a shade of purple that verges on black, in which the unabashed thickness of the brush challenges our ability to recognise the subject, while still offering an expressive likeness. In Untitled (Self-Portrait) (1982), Basquiat organises the composition in thinned and erratic lines, suggesting that somewhere between how the artist sees himself and how he is depicted in the portrait is a face beyond recognition. This reduction of the self is echoed in the presentation of the figures that populate both artists’ political works.

In 1982, Basquiat produced several iconic works that engaged, explicitly for the first time, in the polemical visual language of the Cold War by incorporating the hammer and sickle motif into his figure studies. The sign and symbol for international communism since the Russian Revolution in 1917, for Basquiat this motif may have represented the reconciliation of difference (embodied in the unification of the agrarian and industrial proletariat), and the attempt to bury essentialist identities under the sheer weight of history. Given its charged and historically-loaded political meanings, the hammer and sickle occupy an ambiguous place in his lexicon. For instance, in the diptych Hammer and Sickle (1982), in acrylic and oilstick on canvas, he depicts two men: one holds a hammer, the other a sickle; attention is directed by arrows to sightlines and diagrams of containment; footprints and talon marks on the ground suggest the figures entering, fleeing, or harnessing the capacity for flight. Further major works from this year, such as Untitled (Sword and Sickle) in wax crayon on paper, develop the motif of the transhistorical communist in arms, at once holding objects for their symbolic value while practically preparing for the war to come.

What is extraordinary about Running Communist Man, a work on paper in the present display, is that it was produced a year earlier than these foundational works in Basquiat’s oeuvre. It stands as a compelling artistic commentary on this age of ideological conflict between capitalism and communism, between the rights of the individual and the responsibilities to the collective. 1981 was a transitional year in the Cold War: the election of Ronald Reagan to the US Presidency in January largely brought an end to the hopes of détente between the US and the Soviet Union and with it a new anxiety about accelerated hostilities. Basquiat’s composition speaks to this historical dislocation. The running man, made up of jagged and discordant edges of black, red, and grey, and holding the sickle aloft as though the call to arms of the mob, these symbols designed for unity become––as they also did in the Socialist Realist imaginary––weapons to fight, though the enemy remains in absentia. In contrast to the Hammer and Sickle diptych, in which the two men grant meaning to the other by virtue of each holding half of this bifurcated symbol, this figure is alone in a world stripped of references. His anger is directed off-stage, seemingly into a void, and he thus becomes a powerful meditation on both the new dawn of Cold War geopolitics and an existentialist howl into the abyss.

We might see Basquiat’s Running Communist Man alongside Penck’s Übergang (1980), in mixed media on paper, which translates from German as ‘crossing’, recalling a site of transition, conversion, or the threshold of one life into another. Read biographically from the vantage point of 1980, it is inviting to read Übergang as a reflection on Penck’s border crossing from East to West Berlin, and even his multiple forays into the heaving art centre of New York, as we look to understand what this traversal might mean for the development of his pictorial language. In its exuberant use of colour, which offers something of Matisse’s summer palette in the cutups, Penck depicts a carnivalesque scene of wild Dionysian dance and gesture, as some of his cast of signature stick figures appear to play rudimentary musical instruments. And yet the marks of history return us to what is really at stake here: in the very centre of the composition, half lost amid the chaotic angularity of the whole event, the unmistakable motif of the hammer and sickle is rendered in blood-red curves. If at this time Penck was crossing over from East to West, from a communist state into a capitalist one, then it also stands that he and Basquiat were making new worlds in their works on paper, in a dynamic correspondence that sheds new light on the practice of each artist.